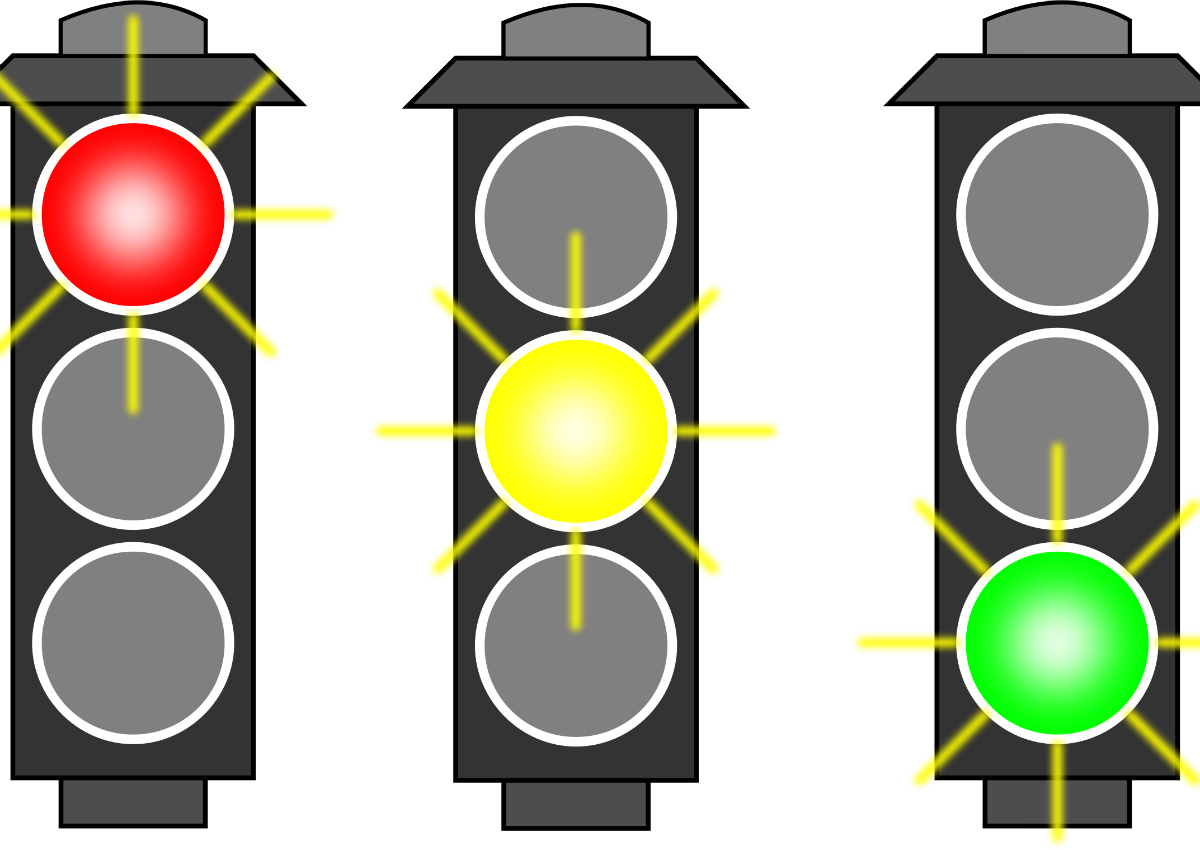

As a means of trying to recuperate a “constructive” relationship with consumers – particularly with those who are more inclined to the idea of a “healthy diet” – and, therefore, to recuperate the desired growth of revenue and turnover, that is currently at a standstill, the six largest multinational processed food companies (Coca-Cola, Mars, Mondelez International, Nestlé, PepsiCo, and Unilever) have decided to offer a so called “traffic light” ingredient labelling system. This system will be offered in Europe and is similar to the one used in England (a red light to indicate products with high levels of fat, sugar, or salt, and yellow and green for those that are “healthier”) but with the strategic difference that serves as an advantage to the more controversial categories. In other words, a seemingly innocent label that is in reality edited to fit the current needs of the food and beverage giants.

Italian food caught in the cross hairs

This move has infuriated many in Italy, beginning with the Made in Italy supporters such as Minister of Agricultural Policy, Maurizio Martina, Federalimentare president, Luisa Ferrarini, and MEP (Member of the European Parliament), Paolo De Castro, who is well documented in the world of industrial agriculture. The why is simple: many of our cheeses, cold-cuts, oils and such have received red lights in England while sugary soft drinks have green lights. Seen from a Mediterranean diet point of view, this situation is paradoxical.

Big food “tempts” Northern Europe’s retailers

It was precisely Paolo De Castro, the first European parliament vice president of the Committee on Agriculture who told Italianfood.Net, It’s evident that there is opposition on behalf of member states to introduce legislation that allows traffic light labels. I don’t even think modifications are being considered, not even at the European Committee level (where regulations are created), but I’ll meet with Vytenis Andriukaitis, the European commissioner for Health & Food Safety, and ask that he takes a stand on this matter in order for him to act in defence of consumers and Made in Italy products. England has previously tried to introduce the traffic light labelling system as a law but then retracted it. The distribution centres were then the ones to “voluntarily” adopt it as a way of avoiding infringement proceedings, which, however, no longer make sense since Brexit. The story remains the same: the move by the six multinational companies is to be seen as a way of suggesting a labelling model that eventually a large supermarket chain will adopt, and we know that in Northern Europe there is specific interest by some retailers for this type of communication with the consumer. Basically, that the same thing happens that took place in the UK.

A system that promotes processed food

The traffic light system has indeed done its job in convincing consumers in England to choose food with green lights more often, at the expense of our products such as Parmigiano Reggiano and Grana Padano and not only. The large multinational companies, by following new food trends, have invested a lot in “light”, “zero”, and “free from” in order to meet consumer requests and by offering this labelling system as well. This new offering though, comes at the cost of those that represent high quality raw materials and place close attention to the processing procedures. We are in favour of labels that indicate the product’s origin – explains De Castro – a completely different concept from one that judges a product simply on its salt and fat content, extrapolating data from all the rest. With this idea, extra virgin olive oil is red lighted while Coke Light is green lighted. I think it’s clear that something isn’t working.

The trick to portion calculations

There is obviously something not quite clear, but the main issue seems to be much simpler than expected. The system studied by the six multinational companies calls for a traffic light symbol, but contrary to the English system it is not based on a standardized 100 grams or ml of a product. Instead, its base for calculation is “a portion”. This is a concept that is easily manipulated and easily misused for which, for example, a chocolate flavoured snack that based on 100 grams would have a red light but would become an acceptable yellow light when based on a 30 gram portion size. This explains the presence of companies that produce chocolate and sweet snacks and crisps within the team promoting this system. This is of no comfort to the products from Italy unless an exaggerated portioning system is used for a wheel of Grana Padano or if Prosciutto Crudo is sold already sliced in order to avoid a red light.