Italy, which is fighting against Nutriscore – the traffic light food label that penalizes extra virgin olive oil and Parmigiano Reggiano cheese – is closing ranks and trying to lobby to convince Brussels to adopt an alternative labeling system.

Now, German farmers are supporting Italy, as are Dutch nutritionists. Above all, Italy has succeeded in breaking the French front. On the one hand, the Paris government, which has notified Brussels of its Nutriscore proposal; on the other, French farmers who are as opposed to Nutriscore ‘red lights’ on their most famous PDO products as Italians are on theirs.

FOOD LABELING, THREE PROPOSALS FOR THE EU

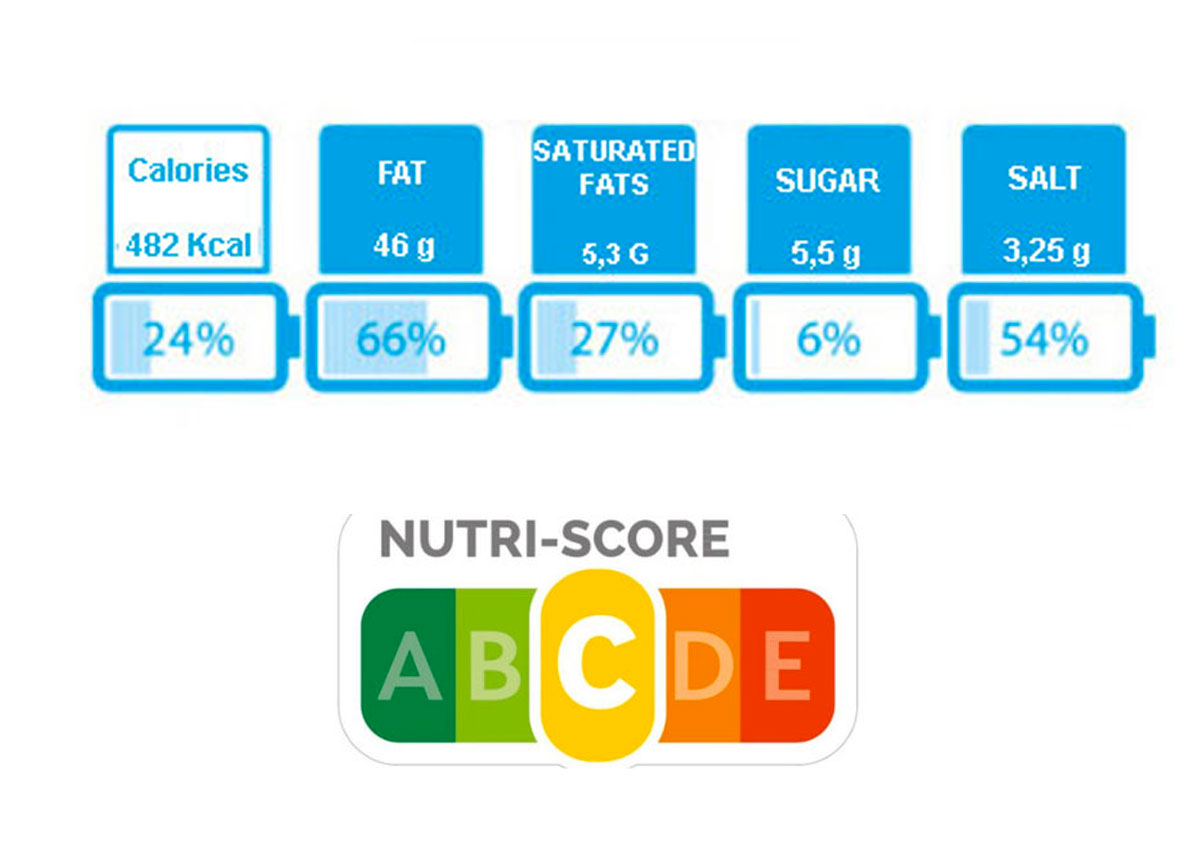

Three proposals on food labeling have currently been notified in Brussels. The first one is French Nutriscore, which along the lines of English traffic lights (even if based on a more sophisticated algorithm) gives food a red to green label depending on its fat, sugar and salt content. “Then there is the Scandinavian proposal, the so-called Key-hole – explains the Italian MEP Paolo De Castro – which in practice puts the green label on products that show certain health characteristics, but does not provide any red label for all others. Finally, there is the Italian Nutrinform, otherwise known as the battery label.”

Nutrinform was recently proposed by the Italian government and is widely supported by all the Italian agri-food organizations, and above all by food industry association Federalimentare. On the French Nutriscore’s side are mainly large multinationals, from Nestlé to Danone to Pepsicola, which have also received official support from the governments of France, Belgium and Germany. Spain supports Nutriscore in an unofficial way, since it has obtained an ‘orange’ label for its extra virgin olive thanks to a modification of the algorithm.

SUPPORTING ITALY’S NUTRINFORM LABEL

Italy received the support of 77 Dutch nutritionists, who expressed their criticism of the French model in a letter addressed to their government.

“I hope and believe that we will arrive at a mediation between the two positions – Mr De Castro said – because it is necessary to correct some distortions in the French model, which does not take into account the quantities of product that consumers eat. The algorithm evaluates the product as it appears on the shelf without considering how it will be consumed. In other words, the potatoes to be fried would have a green label, because the raw material is potato. Too bad, however, that I will eat them fried.”

And what about PGI products? “I argue that they should be excluded from the labeling system – De Castro says – for a very simple reason: European legislation requires them to comply with the specifications. They cannot change the ingredients of their recipes, otherwise they end up violating the law.”