The fate of the free trade agreement between the EU and Canada is in Italy’s hands; and that is why, in all likelihood, CETA (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement) is set to lapse. A few days ago the new Italian Minister for Agricultural Policy, Gian Marco Centinaio, announced that he did not want to ratify CETA. If concrete decisions follow, the entire agreement will lapse and its provisional application – which was triggered on 21 September 2017 pending ratification by all the parliaments of the EU Member States – will be revoked too; at least as far as trade policy measures are concerned, such as the stop to duties.

CETA’S DESTINY

If Italy were to stop at ‘non-ratification’, the treaty would continue to stand, however, even if not for the parts of national competence. If, on the other hand, Italian Parliament were to reject it with an explicit vote, then the CETA could fall for everyone. The FTA with Canada does not contain explicit provisions on the effects of non-ratification by an EU state, and there is no precedent for this. However, Trade European Commissioner Cecilia Malmström recently commented on the effects of a possible ‘no’ to ratification, stating that if there are obstacles to ratification at national level the agreement cannot enter into force and provisional application should immediately cease. There would then be little left to do but to resume negotiations with Canada on a new treaty on trade policy measures. And that is exclusive EU competence.

WHAT THE FTA PROVIDES FOR: FAVOURABLE…

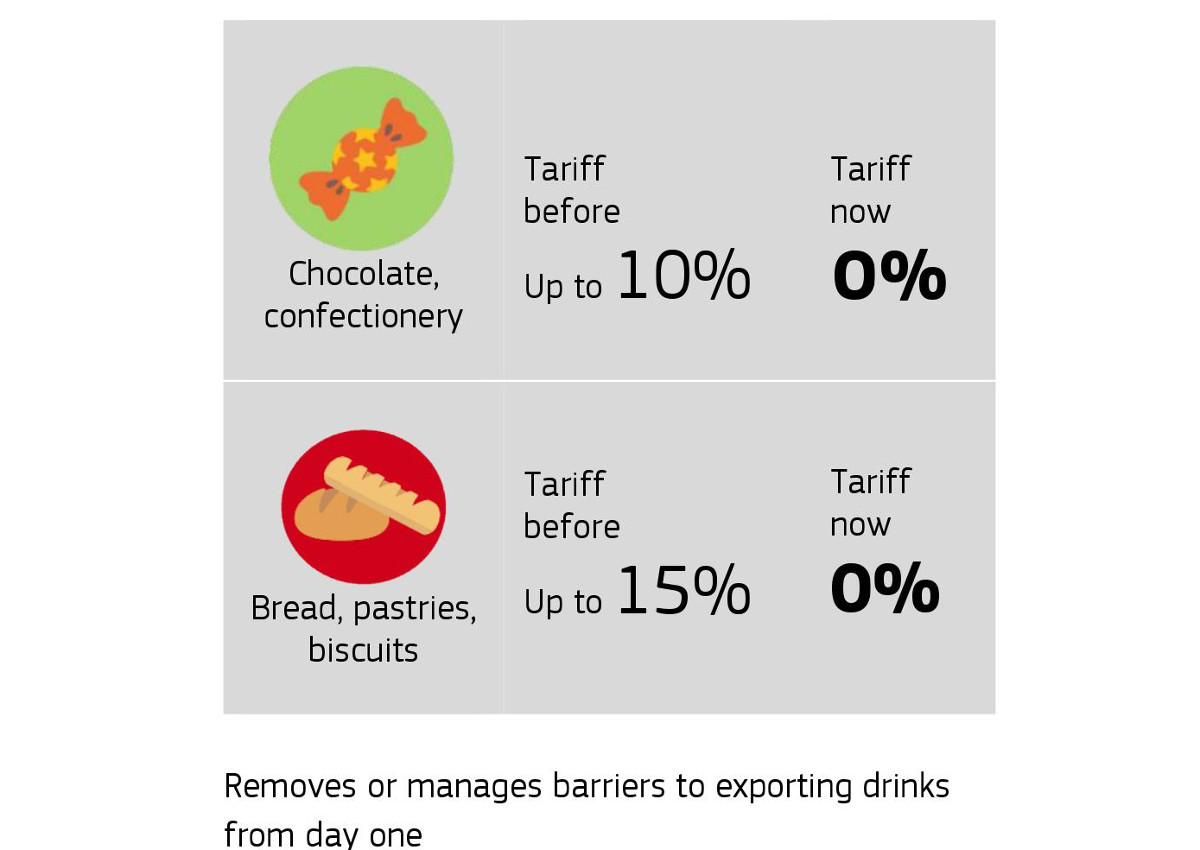

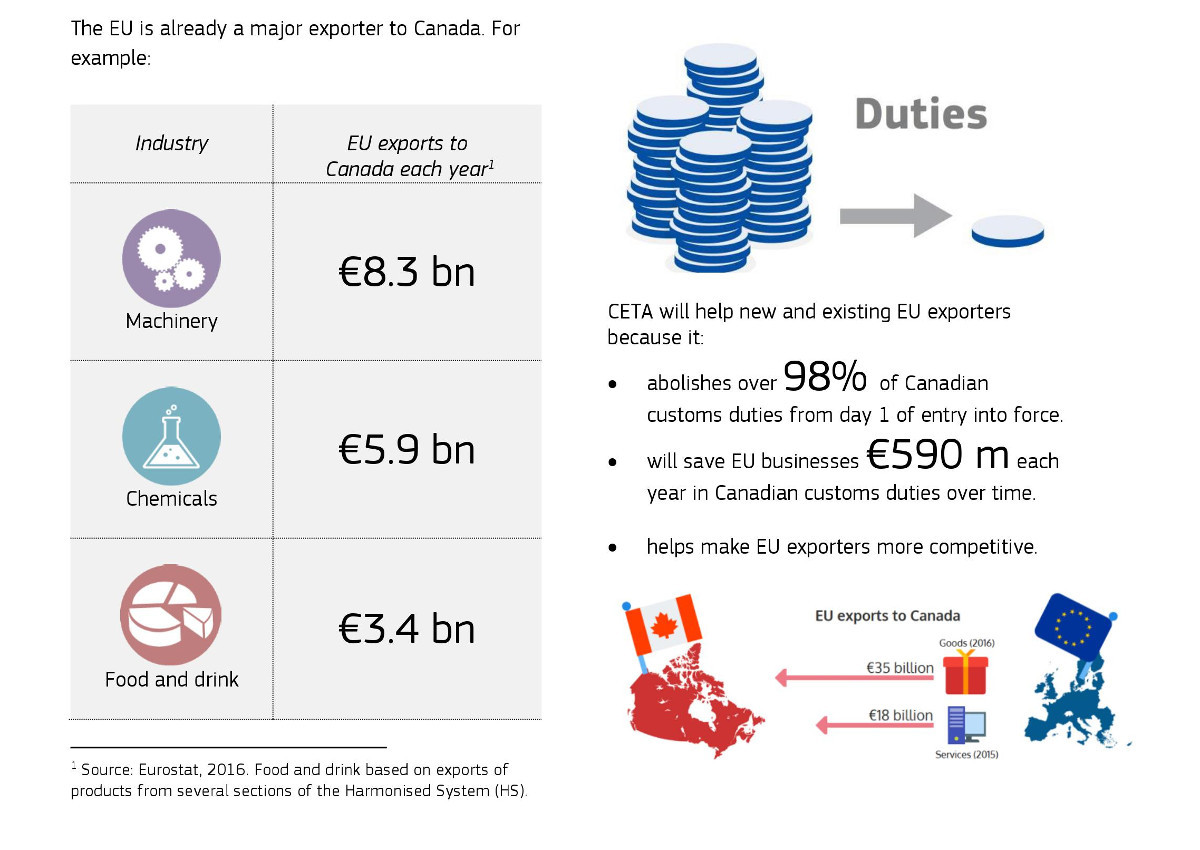

With the provisional entry into force of the CETA (signed on 30 October 2016 by the EU and Canada) the clauses concerning matters of European competence are already in force. Among these, non-tariff measures and the protection of Geographical Indications. According to supporters, this effectively eliminates 99 percent of Canadian customs tariffs for a value of 400 million euros, while at the end of the transition period the figure – according to forecasts by the European Commission – could exceed 500 million per year. In addition, the removal of some important non-tariff barriers and the opening of the public procurement market to European companies should be considered. All this in addition to the recognition of 171 European Geographical Indications (41 of which are Italian food and beverage products). Under the CETA, Canada has undertaken to open up its market to cheese, wine and spirits, fruit and vegetables, and processed food products. All products must comply with EU regulations. In Italy, the agreement provides for the protection of various PDO and PGI products: from Valtellina bresaola to Balsamic vinegar of Modena, from Mozzarella di Bufala Campana to Prosciutto di Parma. European products would enjoy protection from counterfeiting, similar to the one offered by EU law.

… AND OPPOSING THE AGREEMENT

Critics of CETA, on the other hand, point out the risks linked to the arrival on European tables of food products that are treated with chemical additives, GMOs or hormone-treated meat. According to Greenpeace the treaty will give North American companies several tools to weaken European standards on growth hormones, GMOs, washing meat with chemicals, and animal cloning. According to Coldiretti’s President Roberto Moncalvo the decision not to ratify the free trade agreement with Canada is the right choice in the face of a FTA that is wrong and dangerous for Italy. According to the Italian farmers organization in fact with CETA, for the first time in its history the European Union justifies in an international treaty the food piracy to the detriment of the most prestigious Made in Italy products, explicitly giving the green light to counterfeiting that exploit the names of typical Italian food products such as Asiago, Fontina, Gorgonzola, Prosciutto di Parma, and Prosciutto di San Daniele. On the other hand, Parmigiano Reggiano would be freely produced and marketed from Canada under the name of ‘parmesan’, which is a fake.